The network of rock cut shelters helped the Maltese survive World War II. Today they keep the memories of wartime hardships alive. Lest we ever forget.

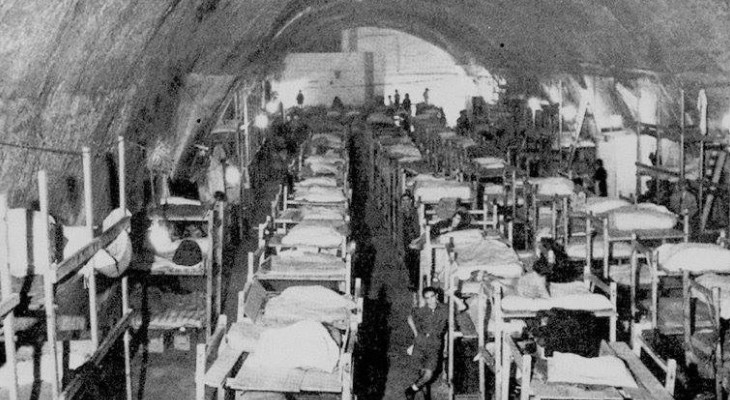

vassallohistory.files.wordpress.com - a public shelter in the disused railway tunnel in Valletta

“…the air was filled with the crash of masonry and the uncanny swirl of blast. The building above was hit. Clouds of dust penetrated the shelter, smothering and half-choking the shelterers with dust, mostly women with babies and young children. Some of the children were terrified and cried, but their mothers open-eyed and stupefied, calmly dipped their handkerchiefs in a pail of water kept in the shelter for the purpose and put them over the mouths and noses of the babies. Then hugging their youngest to their bosom they muttered a silent prayer.” - Foreign Correspondent, Reuters 1942

This was a typical scene at the height of the Siege of Malta during World War II. Fear and hope mixed with noise and dust, discomfort and disease and above all darkness down the underground shelters, as enemy bombs rained relentlessly overhead, destroying lives and flattening the island.

Over 70 years have passed since then, but for those who lived through those days of untold horror, the memories never fade. The network of air raid shelters that were hewn out of the rock remain today a testament to Malta’s resilience and fighting spirit. Some are open to the public not just as a quirky tourist attraction, but also to educate the post-war generation who grew up in an era of peace about the legacy of World War II.

Adriana Bishop

At the start of the war there were very few shelters, and people were advised to seek refuge in basements, under the stairs or even beneath sturdy tables cushioned with layers of mattresses. As the conflict intensified, the excavation of rock-cut shelters gained momentum, and by June 1941 there were 473 public rock shelters with a further 382 under construction, providing protection for 138,000 people. Thousands more also sought refuge in concrete or private shelters. By the end of that year, Government gave permission for private cubicles to be excavated within public shelters, a job which was often undertaken by women and children.

The Malta at War Museum at Couvre Porte in Birgu (Vittoriosa) documents the ordeal of the Maltese and the Allies during the blitz between 1940 and 1943. Situated within the strategic Dockyard Creek off Grand Harbour, Birgu was one of the most heavily bombed places of the conflict, and almost half of it was destroyed. The museum is housed within 18th century army barracks, and sits on top of an extensive network of rock-cut air raid shelters which gave refuge to hundreds of people.

Visitors today are offered the luxury of wearing protective hair-nets and hard hats before descending to the shelters, but in those dark days of war, people were lucky if they got away with their lives. My own parents spent part of their childhood in such shelters and I wanted to experience it firsthand, albeit for an hour and with enemy bombs merely an audio recording.

To say it was a sobering experience would be putting it mildly. As the sounds of people reciting the rosary echoed in the corridors of the rabbit-warren network, I got a sense of the fear and claustrophobia that must have engulfed the shelterers at the time. Efforts were made to retain a sense of order and decorum amidst the chaos of war. Shelter Supervisors and Air Raid Wardens were employed to oversee the day-to-day running of the shelters, Government workmen were paid to clean the shelters and a private cubicle was set aside to be used as a makeshift maternity ward for women to give birth in privacy. Notices were printed on all the walls reminding shelterers not to spit, “commit nuisances” or smoke, but diseases such as scabies, dysentery and tuberculosis were rife.

Adriana Bishop

Electricity was still a novelty in the early 1940s, and Malta’s one and only power station in Floriana was repeatedly bombed. Some shelters were provided with free electricity, but wiring and fixtures were installed voluntarily by the shelterers themselves. Other shelters were simply lit by crude homemade oil lamps.

Those enterprising few who managed to excavate their own private cubicle would furnish it with some personal belongings and home comforts, but the majority had only a bench to sit on or perhaps a primitive bunk bed, as long as they brought their own bedding. Some clearly went to great lengths to ensure their stay in the shelter was as comfortable and civilised as possible, going as far as laying down tiles in their cubicle.

Ancient catacombs dating back to pre-Roman era were also used as air raid shelters, and the Wignacourt Museum in Rabat includes a complex of shelters with two main corridors and about 50 rooms within a network of Punic, Roman and Christian hypogea.

Many inhabitants of the harbour cities were evacuated to rural areas away from the main enemy action to places like Rabat or further away to Mellieha. Today, a popular resort with Malta’s largest sandy beach, Mellieha still bears witness to World War II. Of the 46 air raid shelters in the town, two located near the parish church are open to the public. They feature a small exhibition of tools used to dig the shelters as well as gas masks and ammunition.

Valletta, meanwhile, has a veritable underground city of tunnels and disused wells running beneath the buildings, and many were used as shelters. Part of the network can be accessed via the garden of Casa Rocca Piccola which is owned by a Maltese noble family.